The oak woods and prairies of North Texas depend on the soil and rock below as well as the rains and sun above, so we will start our discussion with those things. If we looked underneath the soil surface, we would see layers of rock gently tilted so that older rock is exposed further to the west of Fort Worth while the younger rock reaches the surface east of Dallas. These layers were deposited by inland seas, rivers, and floodplains, from 300 million years ago in the west to about 50 million years ago in the east.

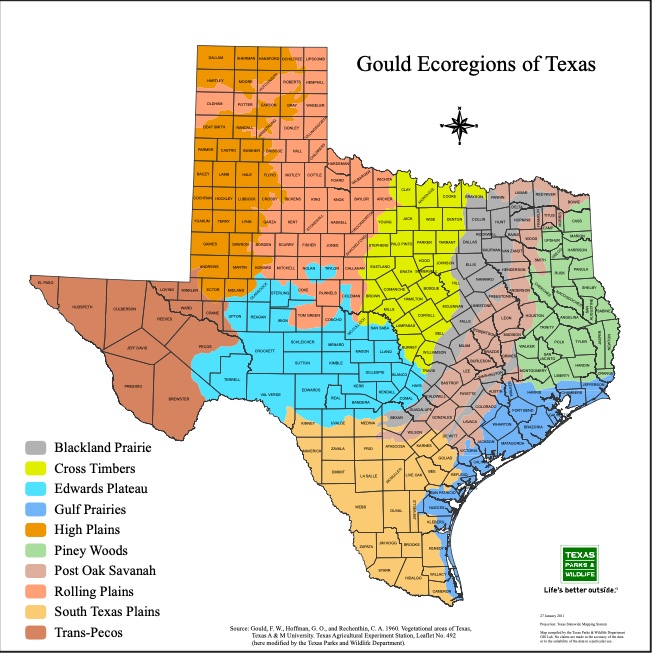

Sandstone, clay, and similar material alternates with limestone across north Texas. Areas with mostly limestone and clay gave rise to a black soil in the Blackland Prairie and in the Grand Prairie to the west. Such soil supports the grasslands found there. In contrast, the two north-south bands of oak woodlands – the Eastern and Western Cross Timbers – grow in more sandy soil (especially in the east) that comes from sandstone. Rainfall is absorbed and held in sandstone and tree roots can penetrate into it for moisture during drought.

Rainfall shapes the plant communities, which in turn shape the kinds of wildlife that live within those communities. In The Cast Iron Forest, Francaviglia reports that annual rainfall is around 40 inches in the east of our region, diminishing to about 25 inches as we go westward. Our climate is changing and weather can be erratic, but it is still true that it is wetter in the east and more arid in the west. And so the prairies of the Blackland region may stand tall and lush, while in the west, grasses are shorter and often a little more sparse. Even the trees are a little shorter in the Western Cross Timbers.

In Prairie Time, Matt White described the original Blackland Prairie as “…a complex patchwork of woods, brushy vegetation, and open grasslands” (p. 5). Trees grew along the corridors of creeks, with prairie often growing where the land was a little higher. The prairie is a diverse community of grasses and forbs (herbaceous, broad-leaved plants). It is full of all kinds of life, including small wildflowers, tall grasses, shorter grasses, vines, ground-nesting birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians (some of whom spend time in burrows along with some crayfish species), and a huge assortment of insects with spiders waiting to ambush or catch them. Such an ecosystem may grow close to the ground, but it is still complex and diverse.

The Blackland grows on that rich, black soil, and settlers soon discovered how fertile it was. The land was plowed for farms and cleared for roads and cities, so that today less than one-tenth of one percent of the original Blackland Prairie remains. Many of those remnants are maintained by conservation-minded farmers, the Native Prairies Association of Texas, and the Nature Conservancy.

The Cross Timbers lies just west of the Blackland, consisting of two bands of woodlands extending southward with a broad grassland – the Grand Prairie – between them. The signature trees of the woods are post oak and blackjack oak. Other species like juniper or hackberry are scattered in places, and low areas near water showcase cottonwoods, ash, and other kinds of trees. However, especially in upland areas, the post oaks and blackjacks dominate.

Both of these species of oaks are adapted for lower rainfall and tend to be drought-tolerant. They don’t grow very tall, often reaching no more than 30 feet. Post oaks often have gnarled and twisted branches. The post oak has deeply-notched leaves with blunt lobes. Blackjack oak leaves are not deeply notched and often have three lobes, each ending with a small spine or bristle extending from the vein of the leaf.

Just as the Blackland is much more complex and diverse than a field of grass, so the Cross Timbers are not continuous oak woodlands. They are a mosaic of woodlands and small prairie openings where little bluestem and other prairie grasses grow along with wildflowers and other forbs such as western ragweed and croton (sometimes called doveweed or prairie tea). Along woodland edges, vines such as greenbrier are common.

The Cross Timbers supports populations of nine-banded armadillos, bobcats, coyotes, white-tailed deer, raccoons, and other mammals. Prairie openings are good habitat for the hispid cotton rat and other rodents. The rodents help provide a prey base not only for such predators as coyotes and owls but also for rat snakes, bullsnakes, and particularly in prairies, the western diamond-backed rattlesnake. Copperheads are common in some places within the Cross Timbers, and Texas spiny lizards hang out (literally) on the trunks of oaks while hunting insects. Days in the Cross Timbers are brightened with the songs of northern cardinals, chickadees, wrens and many other birds. On spring nights near ponds, the calls of gray treefrogs, cricket frogs, and other species can be heard. In the prairies, around ephemeral pools and ponds, chorus frogs call.

A map provided by the Ancient Cross Timbers Consortium shows areas of Cross Timbers from southern Kansas down through Oklahoma and into North Texas

Sources of information:

Chapman, B.R., & E.G. Bolen. 2018. The Natural History of Texas. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Francaviglia, R.V. 2000. The Cast Iron Forest: A Natural and Cultural History of the North American Cross Timbers. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Spearing, D. 1991. Roadside Geology of Texas. Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Co.

White, M. 2006. Prairie Time: A Blackland Portrait. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.