I get up. The kitchen becomes light when I flip the switch. The day starts with some small reassurance of the world’s predictability.

The coffee beans grind with a satisfying aroma, and the coffee tastes good. Things work. Things are OK.

The car starts. Another data point stacks up in favor of a beneficent world.

Against these meager but welcome signs that the world makes sense, there is the news. I don’t want to watch the news, but I am drawn to watch it anyway, the way a traumatized child’s play is drawn toward re-enactment of the trauma. This “trauma play” can crowd out the child’s ordinary, creative, fun play, just as the televised discussion and reporting of bad news can crowd out time that might be better spent elsewhere. But we want to be able to predict what may happen, to know what’s coming. The obsession with knowing “what happened” is a way of trying to make sense of the world and what might happen next.

Oh, good, the trash was picked up, and the recyclables, too. Things are working as they are supposed to.

I think about the health of the people I care about. If there is trouble, I can prepare myself for how to be supportive, and maybe predict how events might play out and what we could do in each situation. Our brains are wired to anticipate the future and try to prepare, in every area of our lives.

Part of our brain can be something like a “situation room,” a place where the experts and leaders gather to try to work their way through a crisis. And if the situation room is always running hot, problems occur. After a while, someone yells, “Turn off the damn alarm,” as the jangling autonomic nervous system keeps us in a panic, but the bell keeps ringing. Everyone sits around the table, exhausted, reviewing the information for the fiftieth time. The more we ruminate, the more dysfunctional the situation room becomes. Exhausted, irritable people do not solve problems well. Neither do chronically stressed or traumatized brains.

I grew up in a world that seemed safer and more predictable.

Stepping back from what I just wrote, it sounds ridiculous, impossible. When I grew up, White State Troopers were beating Black civil rights protesters nearly to death in Selma. Boys were being drafted to go die in the war in Vietnam. We had nuclear attack drills in school, practicing how we would get under our desks to survive hydrogen bombs that seemed likely to fall on us any day. The world would end. How could such a world ever seem safer and more predictable than it does today?

It seemed safer, but it was not. Why did it seem safer – why did the world make more sense in my childhood?

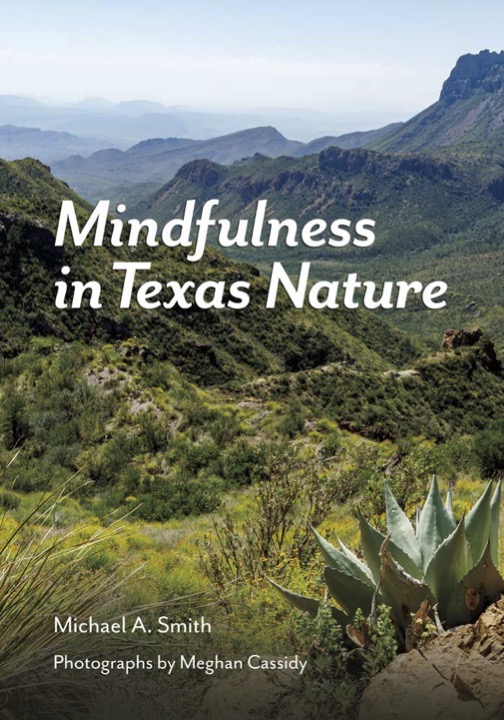

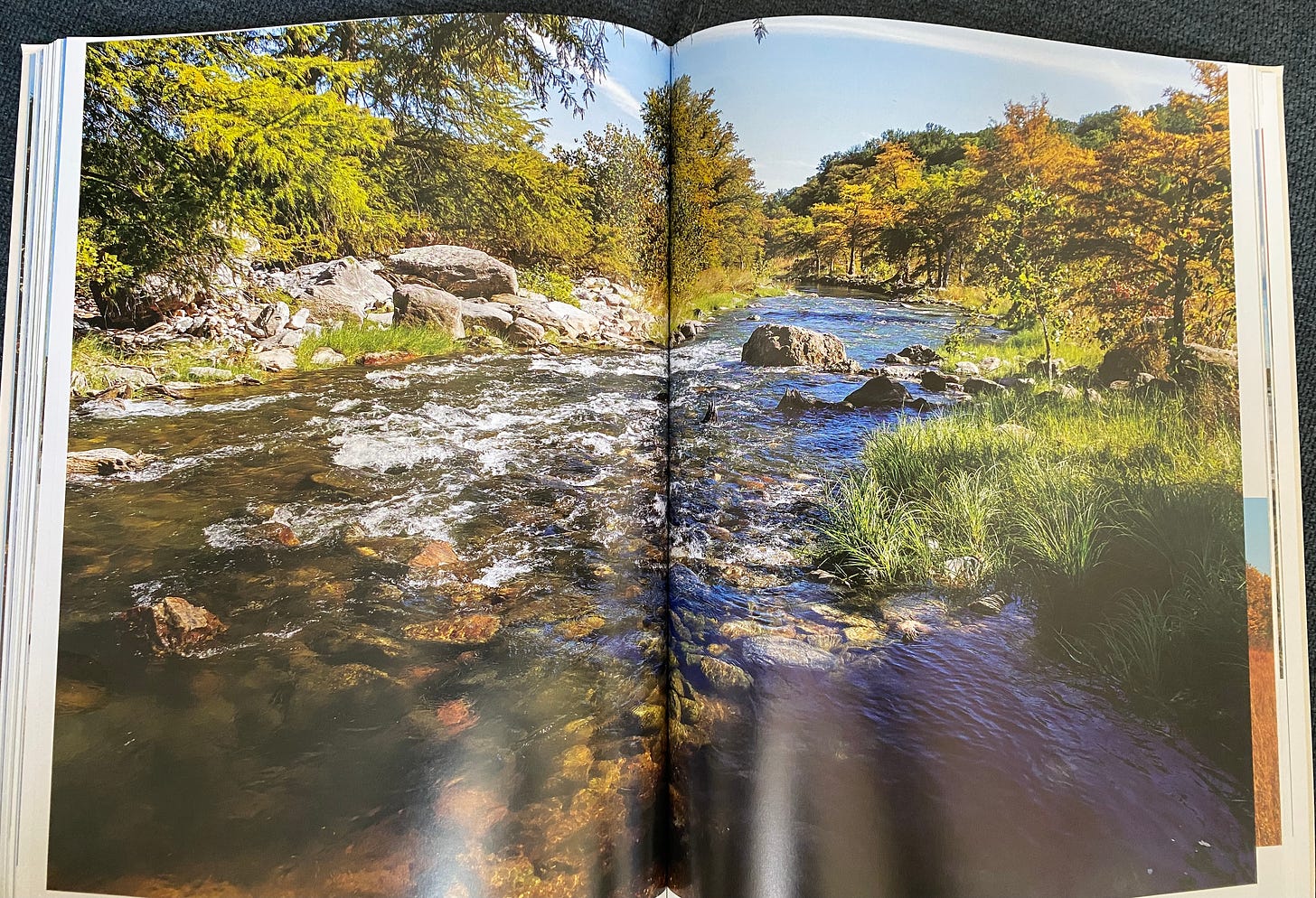

My parents could not take away the threat of nuclear war but they could help support an everyday world in which things happened sensibly, often with happiness and wonder. There was carefree backyard play. There was the sound of waves, the smell of the Gulf, and a young child’s fascination with lightning whelk seashells. And then there were lightning bugs on summer nights, dragonflies in a scrubby vacant lot, and camping in the mountains. The immediate, direct experiences of the day. Having parents to share those gifts and cushion the disappointments and challenges made the day-to-day world a place that seemed mostly safe and predictable. In the fourth grade, if the everyday world is in good shape then nuclear attack drills can be just something that you do, with little connection to the cataclysmic threat and the absurd idea of surviving underneath that desk.

In the everyday world, I watch clouds slide to the north, piling up to great heights with edges lit brilliant white by the sun. They cross the pale blue sky slowly and peacefully. This world, at this moment, is a good place.

Regardless of what the world presents us with, we want it to be sensible, predictable, and safe. Even thrill-seekers want that security after the thrill is over. After the free-fall, after the parachute opens, we want gravity to give us a landing we can walk away from, ready to do something else.

With pandemics, insurrections, and a climate spinning out of control, it is easy to doubt that we can walk away from our landing. Road-rage killings, people assaulting others on airplanes, neighbors stockpiling weapons of war. People gathering to scream utter nonsense opposing a vaccine that could save us. For many of us, the world appears to be less predictable, sensible and safe with each passing year. What do we do with that?

One way of coping with the world’s trouble is to purposefully set aside time for living in the present, the world that we are in contact with each day. We cannot let the world’s troubles make us numb to the little gifts of our everyday lives. Those are the moments in which we visit a friend, listen to a bird, or write a letter (or an email). They are moments of contact with what we see and hear around us, what we touch with our fingers.

My grand-daughter’s beautiful smile draws me into more play. I think what a gift this is, something that makes the everyday world a good place to live.

I know that our everyday lives can be difficult at times. Things break down, a loved one gets sick, we have loss and sorrow at times. But in between those times are the moments when the world offers its most precious gifts of beauty, sustenance, love and joy.

Living in the present is not shirking responsibility or escaping from the world. There are times when we do need to think about the bigger world and contribute what we can to try to bring about change. And when we have done what we can, then it is good to let all that go and spend time living in the everyday reality that we have been given.

I sit and listen to Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 14, completely absorbed in those four interwoven melodies.

(My life as a naturalist and conservationist is balanced by my career as a Psychological Associate. As I wrote a while back, “our lives” is as important a part of this blog as “in nature.” I know that my focus here is our lives in nature – the interrelated ways that humans and other species make their way through the days and years. I will try to stay focused, but sometimes an article will tilt toward the “‘our lives” part of the blog.)