(A writing experiment, with country cemeteries, beautiful prairie, a copperhead, and distant storms. On this visit to the grasslands, I did not take a camera. I intended to experience it without trying to “capture” it in images, although I did have my phone so I suppose I did have a camera. I also did not take a field notebook, but today I wrote some notes. It seemed like the sort of thing that would have, once upon a time, been sent back home as a letter, and so I offer my notes as a sort of letter from the grasslands, with no photos to augment whatever mental images and stories the words might manage to convey.)

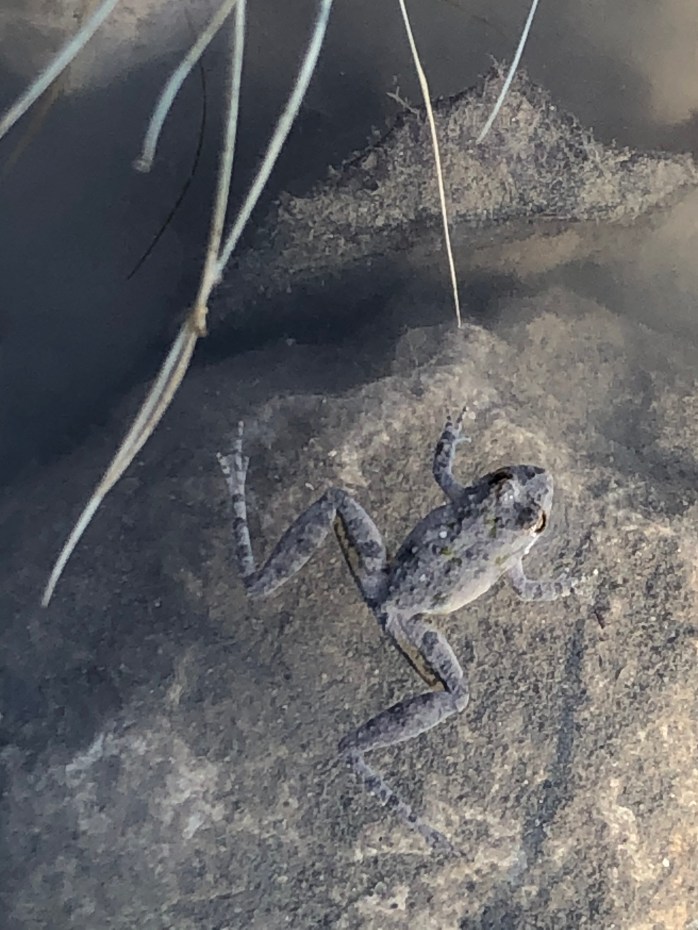

I traveled to Wise County to see how all the rain has affected the prairies at LBJ Grasslands, and I also hoped to sit in the quiet darkness and watch lightning from the line of storms coming in from Oklahoma. In between those things, perhaps I would see a few snakes or frogs crossing the roads after sunset.

On the initial drive through the oak woodlands and patches of prairie, I looped around Ball Knob, a little hilltop and ridge. Tucked away among the oaks, prairie grasses, and wildflowers is a quiet little cemetery, a resting place for people who lived there in the 1700s and later. It is a beautiful place, dotted with oaks and a couple of junipers, with some of the headstones weathered beyond reading. It is comforting to think that they have rested here for hundreds of years in the peace of the cycling seasons. Who knows what it might mean to those who have passed, but for those who remain it is a reassuring reminder of eternal rest. For those who are buried here, each spring sees the return of Texas paintbrush and purple coneflower and each autumn their graves are kissed with a scattering of golden and scarlet oak leaves. The place is circled with an unassuming chain link fence, and there is a small, modest pavilion for anyone who wants to sit for a while. There is a historical marker, but no signs and nothing to disturb the peace. It is perfect.

I drove on, past the historical site of the settlement of Audubon and past the pine grove with its campsites and little ponds. From that pine grove, the road drops down to a broad, mostly open prairie that I walk year after year, following trails across fields of prairie grass and flowers and through post oak and blackjack woodland. Today, after the extended rains that have fallen, the fields were green and dotted with flowers. Red-orange Texas paintbrush pushed up through the green, and meadow pink flowers were tucked away near the ground. Big flower heads of antelope horn milkweed dotted the meadows.

Butterflies and bumblebees visited these and other flowers. The first ones I saw were sulphur-yellow butterflies that fluttered near the ground, stopping at the yellow coreopsis and nervously moving on if I stepped closer. The buzz of the bees is very pleasant to me; I associate it with flowering and the expansion of life, and not at all with pain since these bees will gladly coexist and work around us if we just leave them alone. Everywhere the calls of northern cardinals and other birds made these meadows and woods all the more exquisite. To walk through the grasses and among the flowers, surrounded by bird song and the occasional bee, brings a peace and contentment that I find in few other places.

I wandered for some time, soaking it all in. White-tailed deer peeked at me attentively from below a rise, bolted back a short distance as I continued walking and looked back at me again. Crows scolded me from a nearby line of trees. On a milkweed plant, a monarch butterfly moved among the flowers, took off when I got too close, and then circled back to the plant. The air was laden with moisture and felt warm and close, and the sky was hazy with thin clouds. Cricket frogs began to call, a soft and distant ‘grick-grick-grick’ from a pond somewhere.

Eventually I returned to my car, just prior to sunset. I started to get in and was interrupted by the graceful and acrobatic flight of a couple of birds very close to where I was. They had narrow wings that suggested a swallow, made for maneuvering rather than soaring. The tail feathers were cut into a fork rather than a broad fan, but these birds were too big to be swallows. They swooped and climbed, then one would rapidly pivot, diving down to catch an insect and then pull up and shoot across the meadow, flying out of range only to re-emerge a few moments later. Others joined, until there were five or six birds, each one putting on an athletic show for the earthbound human below. My friend Carly identified these as nighthawks based on their size and the big white spot under each wing.

I drove the little back roads nearby, and at some point came upon a fairly large broad-banded copperhead. I always stop, both because they are beautiful and because they cruise very slowly across the road, very vulnerable to being run over. The glare of my flashlight showed the broad dark and light bands that give the snake its name, dark cinnamon alternating with sandy shade of tan. The finely-sculpted, wedge-shaped head had some of that cinnamon color in the back, divided from the lighter color of the face by a fine diagonal border. Like virtually all copperheads, this one held his head angled up, motionless for the moment, waiting to see what I would do. At such times they are balanced on the edge of a knife, between utter stillness (which would serve them well when camouflaged in dead leaves and grasses) and exploding into frantic attempts to escape. When I slid the snake hook under this one’s head and neck, he bunched up a little, maybe surprised and unsure what to do with this unexplained touching. He then decided it was time to leave, crawling quickly but not frantically off the road.

That was an exciting encounter, despite my having found and interacted with a great many copperheads. I drove down the road with the satisfaction of seeing this beautiful snake and moving it so that it would survive this night. A few miles further, and another snake came into view. This one was a plain-bellied watersnake, dark and sullen but nonvenomous. I took a couple of photos with my phone but did not pick it up. At my approach, the snake pulled itself into a protective coil and lashed out with a quick jab. Watersnakes have no venom but usually do not hesitate to bite if they feel threatened. They leave small scratches, briefly painful and perhaps startling enough to make a coyote, a raccoon, or a human let it go. I nudged him off the road with my shoe and wished him well.

Soon, lightning could be seen along the northern horizon. An oncoming storm front and barometric pressure drop often sets the stage for snake activity, and that was a plus. However, when the clouds get close enough to watch the flashes of light and hear rumbling in the distance, I’m ready to stop and enjoy the experience. Maybe it is a contradiction that I respond to distant storms as gentle and soothing while at the same time representing immense power. Which part appeals to me, or is it the idea of such a powerful thing being capable of soothing? In any case, the faraway thunder is a lullabye and the flashes of lightning no more threatening than the moon or a shooting star. I pulled off onto a Forest Service road and stopped the car so that I could stand in the quiet darkness and watch.

It was very dark behind the tree line and then a flash appeared from within the clouds and rolled from one to the next. Then it was dark again until nearby clouds were briefly lit by what seemed like an internal fire, outlining the clouds in front of it for an instant or two. It was completely quiet. Radar showed the front still had not crossed the Red River; it was too far distant for thunder to be audible. Earlier, the air had felt warm and saturated, but now some cooler breezes were stirring. I stood in the darkness for a while longer, watching the random flowering of distant lightning and enjoying the quiet.

Be well and happy. Visit the grasslands when you can.

Michael Smith