On a day when the temperatures reached the upper 70s, under bright sunshine, we took a walk and a wade through a cold creek, ten days into winter (using the December 1st meteorological beginning). It was delightful.

It probably seemed ridiculous to Barbara’s kids when we arrived at the creek bed and found much more water flowing than I had predicted. They followed me upstream a short distance until I reached a broad pool that would require serious wading. I volunteered to go ahead and see how deep it would be, and when it became thigh deep, frigid and numbing, I glanced back toward them. Barbara was gamely ready to give it a shot; Nicholas stood with his infectious grin as if to say, “you gotta be crazy.” Dani looked like she was figuring out how she could quietly slip back to the car.

“OK, well how about downstream?” I asked, and everyone quickly assented. By the time we got back to our entry point, I could not feel my feet. Above the water was a different story. There could hardly be a more comfortable, sunny day as we made our way downstream over dry limestone rock and water only an inch or two deep.

I talked about finding fossils in this white Cretaceous limestone, including echinoids (like sea urchins), conical snails, and ammonites. The most dramatic fossils are the ammonites with their ribbed, coiled shells resembling today’s nautilus and related to the squid or octopus. I rarely find intact ammonites but it is exciting to find even a portion of one. We soon found a fragment or two, along with some fossil oysters and other bivalves. Nicholas soon found a living modern bivalve, that is, a freshwater clam that a friend identified as a species originally brought here from Asia.

The water got deeper, and that give me a chance to net up some fish for us to examine. What I netted were mosquitofish, a sort of minnow that often swims in groups searching for something edible on the surface of the water. I showed the others the little ones among the wet leaves in the net and mentioned one of the things that charms me about these fish. While they are basically colorless, when seen in the right light a blue color is evident. It might be a sort of iridescence, though it seems to come from within the fish. I noticed it when I first caught and kept them as a teenager – mosquitofish and I go back a long way – and it is still one of the first things I think of when I see them.

Throughout autumn the leaves fall, spinning and sailing down to the water’s surface where they become saturated and sink to the bottom. Bur oaks, beeches, red oaks and sycamores all contribute to a beautiful collection resting under the clear water. The pale silt from limestone and shale lightly dusts these leaves, making them the creek equivalent of a sepia-toned photo.

We found a place where the creek has cut straight down through sand and shale, forming a sort of wall. Some layers and spots erode more easily, so during floods the current has carved a shallow pocket into the wall, leaving a bench of gravelly soil that we sat on for a while. I wrote notes while Barbara sketched sections of ammonite and leaves. Dani found a comfortable place in the sun.

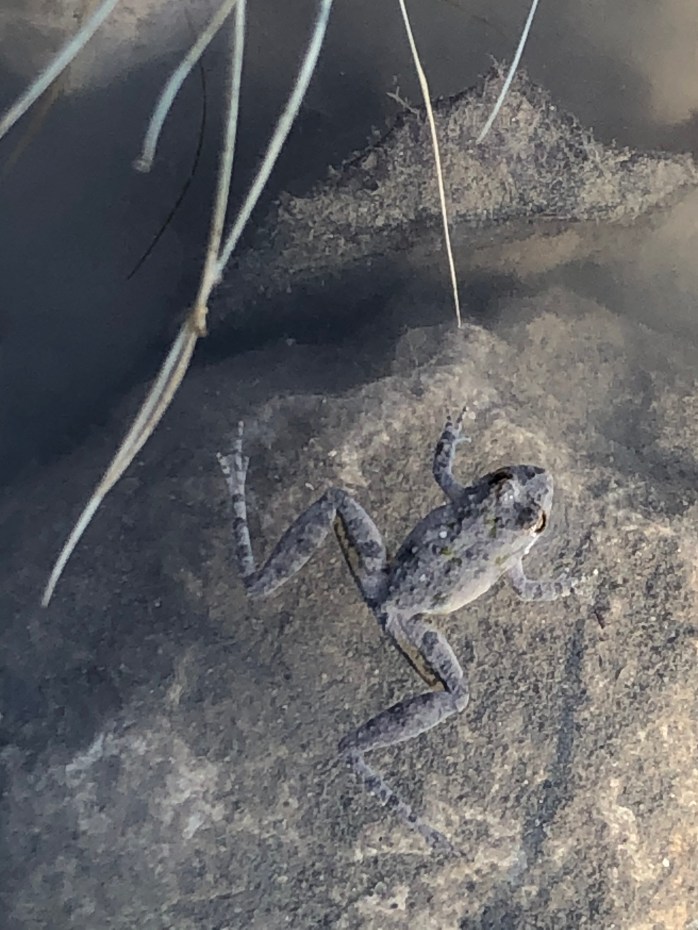

As Dani enjoyed the sunshine, the rest of us waded further downstream. Because it was sunny, the cricket frogs were sitting at the water’s edge, waiting to ambush tiny invertebrates to eat. These thumbnail-sized frogs may seek shelter when it’s truly cold and when it’s overcast or raining, but otherwise they are active year-round in our area. In summer they seem impossibly fast, jumping into the water and swimming to some place of concealment almost faster than your eyes can follow. Today their “cold-blooded” metabolisms could not generate that kind of energy.

Nicholas caught a couple of cricket frogs by hand, a pretty cool trick in summer but much easier today. When one slipped away and jumped into the creek, it hung in that clear, numbing cold water and floated over the rocks and leaves of the creek bottom. A few minutes later it would be sunning on the creek bank and hoping for a little hunting success.

Further down the creek, Nicholas spotted a small bird getting a drink at the water’s edge. It dipped it’s slender beak into the water a couple of times and soon flew away. I got a good photo but struggled to know this bird’s identity, but with the help if iNaturalist I found that it was a yellow-rumped warbler. The narrow beak, a bit of a white ring around the eye, and the wing bars helped, but there was only a suggestion of a yellow patch on its breast. It turns out that in its winter plumage, there’s not a lot of yellow to be seen, and this bird’s position obscured whatever yellow may have been evident on its rump.

There were no clouds in the sky, and in shallow riffles the sun and water created the most beautiful patterns of light. Each ripple in the water focused sunlight onto the pale limestone creek bottom in a shimmering, dancing line. Sometimes they moved in the direction of the current and they swirled when the water was disturbed as it passed through troughs and over stones. At times through some trick of the light they seemed to move back against the current. It might be a small and ordinary thing to watch what the bright sunlight creates in clear, moving water, but it was a wonderful gift today.

And then it was time to head back. This creek has been such a treasure over the fifty-plus years that I have visited it, and I look forward to seeing another spring there when the new green growth and spring rains transform it into one more wonderful version of itself.