… and at least one amphibian

My interest in nature has been dominated by reptiles and amphibians (herps) starting when I was nine or ten and the girl across the street invited me to come along and find garter snakes in Colorado. I was active in herpetological societies twenty-five years ago and I’ve been teaching incoming Master Naturalists about these animals for some years. I’m interested in the “big picture” of ecology and natural history, but herps are still an important focus.

Herp conservation is very important to me. If you’d like to learn more and support some important work, please check out the Amphibian and Reptile Conservancy and the Orianne Society, among other organizations (such as Texas’ own Texas Turtles). I’ll be giving talks about reptile and amphibian conservation in Texas over the next few months, and while preparing, I’ve added some species profiles to the downloadable pdf files on my herpetology page.

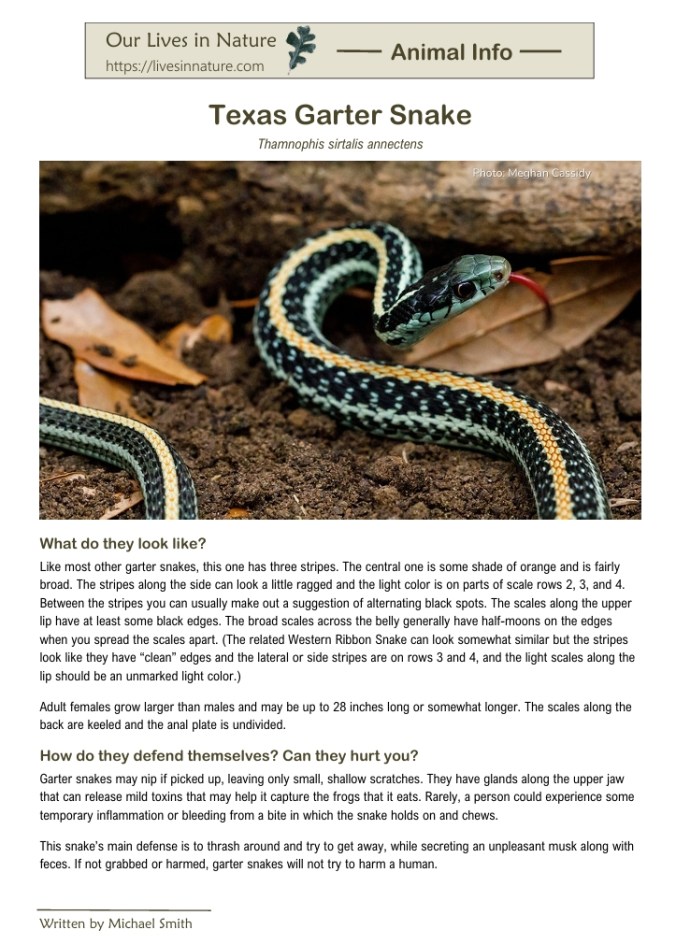

Among them is information about the Texas Garter Snake, a subspecies of the “Common” Garter Snake. Across the years, I have found a handful of Texas Garter Snakes, and they turn up occasionally on iNaturalist, but as far as I can tell they have never been common. There seemed to be particular spots or areas where they had viable populations, but even in those places a search for them was always hit-and-miss. That turned out to be the case in 2013 and 2014 when a group from UT Tyler started a project to investigate its genetics and preferred habitat. They did not find any, and had to rely on a few museum specimens in order to finish the project (published in The Southwestern Naturalist in 2019).

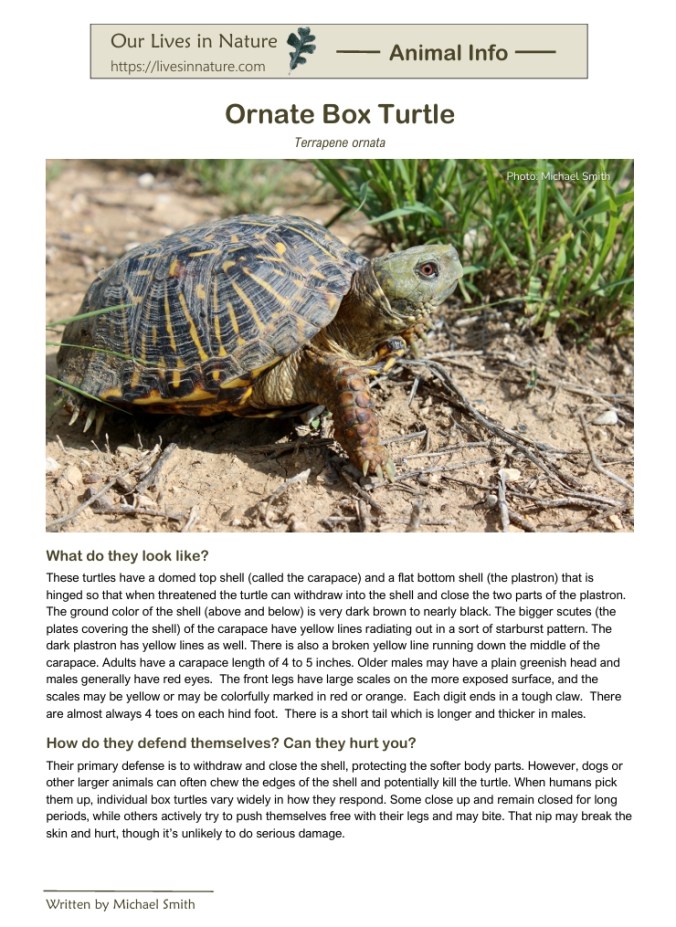

Another profile covers the Ornate Box Turtle. I have loved box turtles since I was a kid (and at least half of Texas would say the same thing, until they became uncommon enough that kids didn’t get many chances to see them). They have suffered from habitat loss and fragmentation, road mortality, and the unfortunate tendency of our species to want to collect and keep interesting and cute animals. In recent years, Texas protected box turtles from commercial collection. However, people still pick them up and take them home. Like turtles generally, their success depends on living long lives once they become adults. Collecting one is like running it over on the road – it is “dead” to the reproductive population of turtles.

And Texans of a certain age recall when the Texas Horned Lizard could be found in back yards and local parks. In the 1960s these places were often dotted with Harvester Ant colonies with a big bare circle of ground around the opening to the colony. These were the horned lizard’s food, and when people poisoned the ants (and later when the fire ants largely replaced them), there was nothing for horny toads to eat. Also in the 1960s, large numbers of these lizards were collected and shipped off to the pet trade where they inevitably died. But probably the biggest deal, according to Andy Gluesenkamp, was the loss and degradation of habitat. Native Texas prairies, with bunch grasses, open areas, ants, and the right combination of shelters and wildlife “neighbors,” were great for them. Monoculture pastures of non-native grasses, the increasing network of roads, the invasion of fire ants, and other factors have eliminated Texas Horned Lizards from many of the places where they used to be found. (Gluesenkamp led the San Antonio Zoo effort to captive breed and release young horned lizards in suitable habitat – an effort that is working.)

So far, the sole amphibian I’ve profiled is also one that biologists are concerned about. There is little real data concerning how Woodhouse’s Toad is doing, but it is the species that many of us used to see on spring and summer nights in North Texas. It has largely been replaced by the Gulf Coast Toad, but away from the cities there are places (like the LBJ National Grasslands) where Woodhouse’s Toad seems to be the predominate species. Overall, the species is considered secure, but are we sure? Wildlife agencies and universities have limited resources and cannot study everything. Everyday folks documenting what they see on iNaturalist help a great deal, but there are still enormous gaps in our knowledge of the status of most of our herps.

There are other species with these two-page downloadable pdf profiles, including the Texas (Western) Rat Snake, the Great Plains Rat Snake, the Long-nosed Snake, Rough Earth Snake, and Checkered Garter Snake. I hope you’ll use them to share with home schoolers, scout troops, or anyone else who would like them. I’d be happy if you’d like to leave a contribution, but if you can’t, that’s fine. And maybe leave me a note about anything else you’d like to see. Our venomous snakes are briefly summarized in my “Identification Guide to Venomous Snakes of North Central Texas,” found on the same page.