With one more week of summer, I wanted to walk in the LBJ National Grasslands. Summers there can get really hot; I will never forget a midsummer walk years ago in these grasslands. I was out with some herpetological society members on a day when the temperature was supposed to be more moderate, and everyone was probably on the verge of heat exhaustion. At least one member was feeling faint, and we made our way back to the cars by walking from one patch of shade to the next.

This day at the grasslands would get no hotter than the mid-90s. That’s how warm it was at 2:00pm when I arrived at a trail taking me into open fields and oak woodlands. There were patches of prairie dominated by Wooly Croton, a slightly fuzzy plant whose seeds are sought by doves, among other birds. And so, another common name for it is Doveweed. It is also a host for caterpillars of a beautiful butterfly with the strange name Goatweed Leafwing. Accordingly, another name for this plant is Goatweed. All those names can get confusing (it’s also called Hogwort by some) but the names tell interesting stories. In other areas, Western Ragweed was common. Allergy sufferers may wince at the mention of this plant, but consider the scientific name of its genus: Ambrosia. It may not literally be the food of the gods as the name suggests, but if you crush a leaf between your fingers, the smell is wonderfully aromatic.

There are plenty of native grasses, including Little Bluestem, which is easy to recognize because its blue-green stalks with pale smears of magenta stand so straight and tall. Today, some patches were shoulder to head high, giving a particular color and texture to some parts of the prairie. Switchgrass is common in areas that get a little wetter, growing in big green clumps.

The land gently rises and falls, with swales and ridges that are a part of the natural shape of the earth. In most places, the soil is very sandy and erodes easily. It is not unusual to come across a spot where the ground suddenly drops into a gully or maybe a spot where rainfall gathers into a little pond. In other places, humans built embankments years ago that created ponds either for cattle or to slow the runoff and conserve soil.

At the fork in the trail, I turned and followed the bare sand and clay track to the north, through stands of Post Oak and Eastern Redcedar and out into grassland openings, grateful for the breeze as well as for the bright sunshine. Along the trail were clumps of Bitterweed, with thin leaves and stems and bright yellow flowers. In each of those flowers, the central bowl-shaped disc is full of tiny yellow disc florets, and arranged around it are the ray florets (most of us are taught to call these structures the “petals”), each one scalloped at the edge. The plant is said to be bitter, so that if cattle must forage on them the cows produce bitter milk. But Bitterweed is a familiar and welcome sight to me, and I often find them blooming deep into winter.

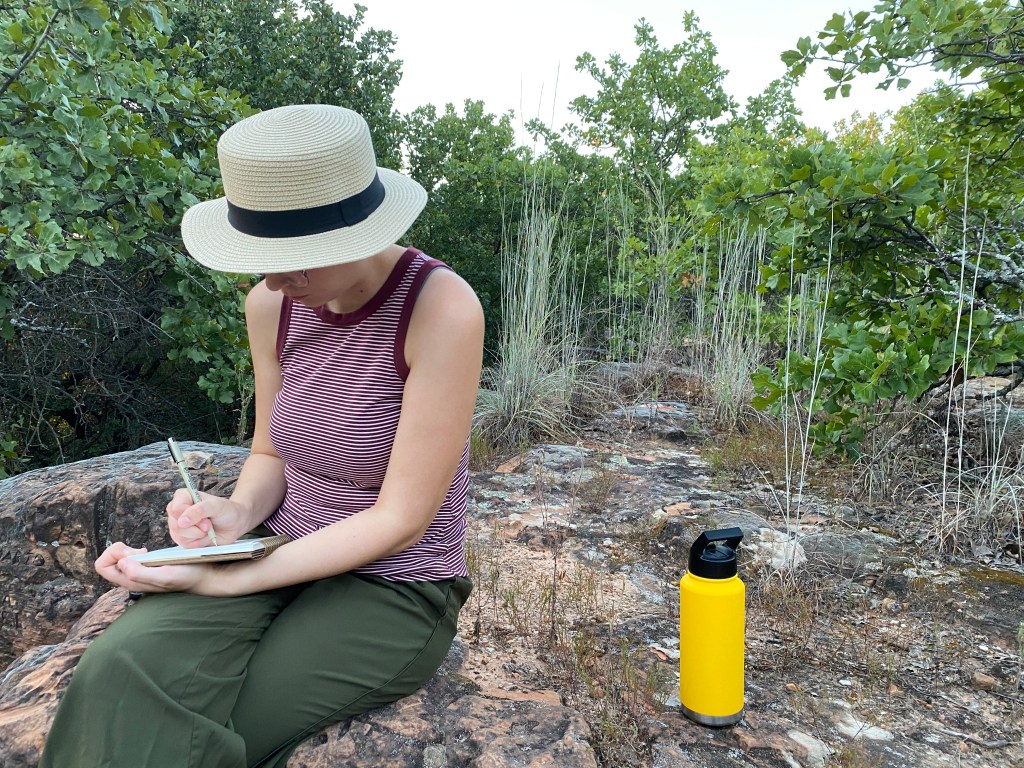

I sat in the shade of an oak and wrote for a bit and then decided to turn back. I became increasingly grateful for breeze, and thankful for the bright sunshine only in a more abstract sense. It’s true that it was a beautiful day, but the day was determined to show that it was still summer for another week. I found myself looking down the trail for the next spot of shade and heading for it. Perhaps my age is catching up with me, or perhaps it was poor judgment in choosing midafternoon to take this walk.

Down the road was the big pine grove in Unit 30 where people love to camp. And it is a wonderful place to sit and listen to breezes sifting through the crowns of those big Loblolly Pines. Not only that, it is dotted with a number of ponds with turtles and frogs. That made it a perfect place for me to sit beneath those trees, breathing the smell of pine trees and listening to breezes and birds. The grove is a good crow hangout, and I heard several. The identification app Merlin also heard Great Blue Heron and Northern Cardinal.

I walked to a spot near one of the ponds and sat beside a big pine tree and across from another. My camp stool rested on a mat of pine needles and dropped twigs that had accumulated over the years. At the water’s edge were the bent but mostly straight trunks of twelve to fifteen understory trees, and beyond was the water, brown from the sand and clay of the soil. On the surface of the water were mats of Floating Water Primrose and clumps of small reeds.

As I watched for the movement of a frog or turtle, I saw skimmer dragonflies dart this way and that. By now it was 4:20pm and the sun was getting lower and the slanting light more golden. Some insect trilled a steady “wrrrt-wrrrt-wrrrt” – almost but not quite like a gray treefrog. Occasional concentric ripples appeared in the water, maybe from fish or some invertebrate. Between the insect trills and the low, hushed sound of breeze in the pines it was very quiet.

It was peaceful here. The smell of pine needles, the lullabye of the breeze, ripples in the water, the sudden appearance of dragonflies; I was very lucky to be there for all of it. And while I’d like to share all of it, I am thankful for the solitude.

At 6:00pm I had moved to a limestone ridge in Unit 71, with a clear view to the west. Here, the Leavenworth’s Eryngo adds some spikey purple to the landscape, and False Gaura is scattered around with flower clusters looking like popcorn waving in the breeze. During the next hour, the sun was obscured behind some clouds near the horizon and it began to feel like the day was ending. Although there were some distant noises, a pump somewhere, an occasional car or jet, it seemed very quiet. No sounds of birds or insects. In the blue sky to the south, a few wispy clouds were drawn out like a downy feather.

The sinking sun reached a point where it was behind some clouds, lighting them from behind so that they looked like islands and archipelagos in an orange sea. The ones several degrees up from the horizon were orange, while the ones just at the edge of land were dull red-orange.

Out of all this, I began to hear gunfire. Somewhere nearby, someone was shooting a rifle or shotgun. When visiting the grasslands, I understand that hunting is allowed with the restriction that only shotguns are allowed (not rifles, where stray bullets would be more dangerous) and shooting is not allowed near trails and campsites. I find bullet casings at the grasslands frequently, so I know that people who like to shoot may not care about the rules. And so, hearing gunfire is a real concern for me. I moved further south along the top of the ridge, and after a while I heard more gunfire – not very close, but not very far off. I sat on the other side of my car from where the sound seemed to be coming.

Forest Service land, including the National Grasslands, are supposed to accommodate various uses, including everything from logging and drilling to hunting and fishing. I understand that public lands cannot be reserved just for one kind of user such as birders or naturalists. However, some kinds of use pose no threat and little chance of degrading the land. Other uses could result in someone being shot or patches of habitat being bulldozed and potentially poisoned for gas and oil drilling. Maybe the “multiple-use sustained-yield” law that opens forests and grasslands to all these uses should have taken into account these different impacts on the land.

Hunters and gun owners might claim I was overreacting. I must acknowledge that the statewide hunting accident data in Texas for the past three years show one fatality each year and between 10 and 18 non-fatal accidents per year from 2022-2024, a lot of them while dove hunting (it is currently dove hunting season). Statistically, I’m safer at the grasslands than I am on Texas highways, where there were over four thousand fatalities last year.

At 7:25pm that orange, red, and blue sunset sea was more brilliant and well-defined. And every minute changed the view. The sun was now fully hidden, shining down between the cloud and the horizon like fire, glowing red-orange in the mists. Then the ball emerged below the cloud, reaching for the horizon.

Ten minutes later, a cool breeze came up, steady this time. With it, the beginning of a pulsing, buzzing insect song. The last burning ember of the sun disappeared at 7:37pm, leaving a brilliant sky. The edges of the clouds were left like burning scribbles, and closer to me the undersides of clouds were lit in gold. Even the tattered clouds overhead were lit up in yellow-orange. Just a bit later, looking back from the west the clouds were blue-gray brush strokes edged in pink and orange. The sky was deep blue overhead but pastel all the way around the horizon, perhaps from light pollution and haze.

Nearing 8:00pm, still not full dark, stars were not yet visible. The color had left most of the clouds and the ridge was quiet. Just as the summer was ending, the day also was coming to an end.