I visited Sheri Capehart Nature Preserve today, much as I have for the past ten years. I followed the trail to the sandstone ridge at the top of “Kennedale Mountain,” walked around the hill and down the boulder trail and back to the west. Despite one recent rain, it is dry at the preserve and many of the plants are drooping. On some sumacs, the leaves are giving up and becoming dark and shriveled. Some others are turning colors and autumn has barely begun. I suppose it reflects the stress of recent hot and dry conditions. Soon, the rest of the sumacs will turn bright red and orange, if they can hold out until the days get a little shorter and the temperature cooler.

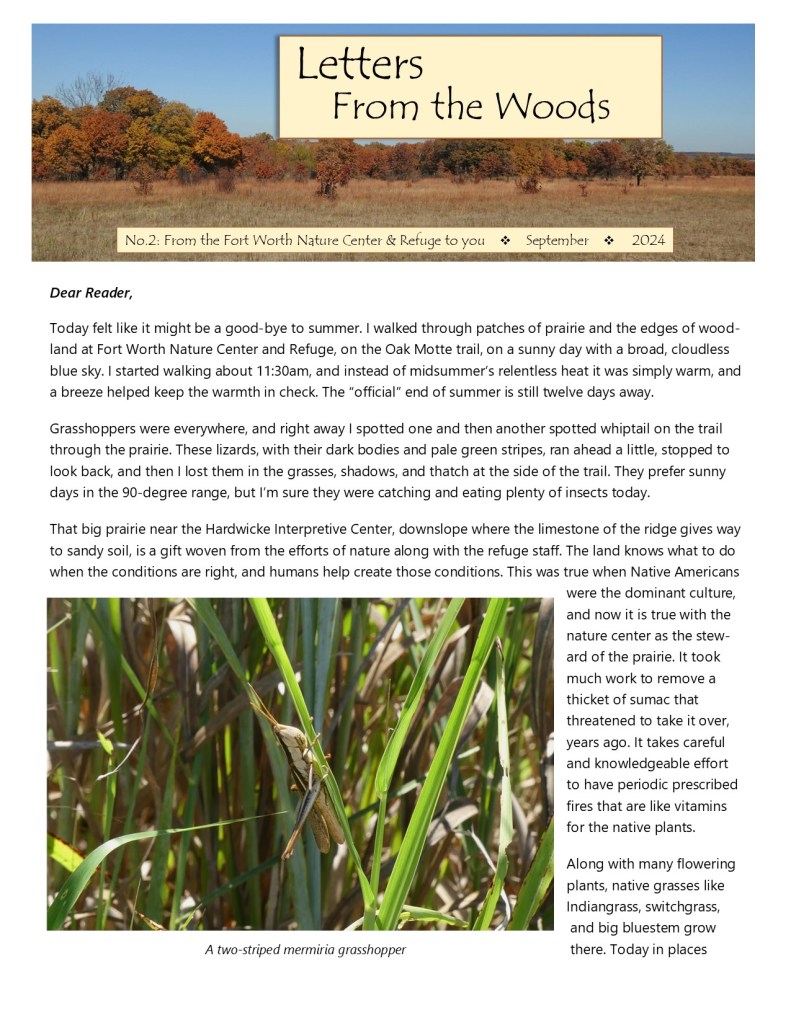

As I walked, a medium-sized moth flew across the trail in front of me and landed on an oak’s trunk. I was able to get a photo of this slightly fuzzy delta of moth beauty, and then it flew away. Those wings near the head were frosted gray with vague scalloping black lines and then irregular bands of darker color, then a brown band and alternating colors like soft squiggles. Finally there were dark/light dots – one above each scallop of the wing’s edge, with a pattern like tiny feathers. There were a couple of warm reddish-brown spots at the edge of an arc of dark color, symmetrical on each wing. The subtle patterns and colors were beautiful.

The iNaturalist app identified this as a “Sad Underwing,” with the scientific name Catocala maestosa. The genus (Catocala) means essentially “beautiful below” and the species (maestosa) is a reference to “majestic.” The underwing moths have hindwings of a contrasting and often beautiful color, thus “beautiful below.” Those hindwings are covered by the forewings when the moth is resting, and that explains the “underwing” part of the name.

Many underwings have splashes of orange or pink color in those hind wings, which might startle a predator when the moth suddenly takes flight. But this species, the sad one, has hind wings that are very dark brown to nearly black. Some sources suggest that this is the reason for the “sad” in the name, either that the darkness reflects something sad or perhaps that being deprived of color is a reason for sadness. The moth had no comment about it.

From what I can see, the larva – this moth’s caterpillar – is even more camouflaged than the adult, mottled brown and gray to look like tree bark. Multiple sources say that the caterpillar feeds on three tree species: Water Hickory, Pecan, and Black Walnut. The moth is found from eastern Canada down through roughly the eastern half of the U.S., including Texas. NatureServe says that it is found in woodlands and river floodplains.

Walks through this and other parts of the Cross Timbers are often like this. Some small treasure crosses your path somewhere, a moth or bird or flower with a fascinating life story and a beauty that you discover by staying with it for a minute, looking closely, and wondering about it. I have probably walked by underwing moths before and missed all this. I’m very glad I noticed this one today.