The creek bed was slippery as Elliott and Kate waded upstream. Ahead of them they could see several Sunfish, huddled in one spot where the clear water was a couple of feet deep. Then the blue-green fish decided that the two humans were getting too close, and they made a break for it, darting one at a time past Kate and then practically between Elliott’s legs.

“I could have caught one in my hands if I was fast enough!” Elliott claimed. He added, “But I’d probably have fallen on my butt. This spot is really slip…”

Before he could finish, his legs slipped out from under him and he really did land on his butt. The water cushioned his fall, and he sat on the algae-coated limestone, spluttering. Kate came back to help.

She extended her hand to him. “If I fall in, I swear you’re going back down too,” she teased.

Elliott managed to get up without pulling her in, and they kept wading upstream, past schools of little silver fish and a small Red-eared Slider turtle hiding in the shallows. His shorts and shirt were wet, but they would soon dry in the sun. And to have Kate take his hand and help him get back up, he thought it made falling down worth it, though he wasn’t going to say that to Kate.

It was October, but in Texas all that meant was that it was warm rather than hot. As Halloween got closer there were no golden or orange leaves, no autumn color yet although some leaves were falling just from being worn out by a long, mostly dry summer.

At a bend in the creek, the two of them waded out onto the exposed white limestone bank of the creek. Another, higher layer formed a sort of bench where they could sit in the shade, facing the water. Elliott went through his backpack, which had stayed mostly dry inside when he went in the water. He found his journal still sealed in a plastic bag, protected against just that kind of accident.

Kate looked back at him. “Are you getting your journal out? This looks like a pretty good place to do it, right?”

Elliott agreed. The teacher in their 10th grade science class had given this as an assignment: Take a notebook somewhere out in nature and write or draw about what you find. Kate liked this creek and so after they got the assignment, she asked Elliott to come along.

Each of them opened their notebook and wrote the date at the top, followed by the location of the creek and the time they started walking and wading. There were a list of prompts included with the assignment, suggesting what to include.

“Let’s see,” Kate began, “there’s weather stuff. The sky is kinda deep blue today, with a few clouds, right?”

Elliott looked at the clouds. “Yep. I think those are high clouds, a forget what you call them, but they’re sort of like a little bit of milk swirled across the sky with the tip of your spoon.”

“OK, ‘milk clouds,’ I’m sure that will win us the weather expert prize.”

“Whatever,” Elliott responded. “Remember she said it doesn’t have to be technical. She said just describe, put what you experience into words.”

“’Elliott stinks like creek water.’ There, I’ve put my experience into words.”

Both of them were quiet for a minute. Then Kate said, “OK, sorry, I’ve written about blue sky and swirly clouds. Did you bring a thermometer?”

“No, but I’m going to check the nearby weather.” Elliott pulled out his phone. “So it’s 78 degrees nearby. Feels warmer when you’re out in the sun, huh?” Then he pulled a section of his T-shirt up and sniffed it.

“That does not stink.”

Each of them wrote in his or her journal for a while. And then Elliott asked, “Remember that big white wading bird we saw back there? Do you know what it was?”

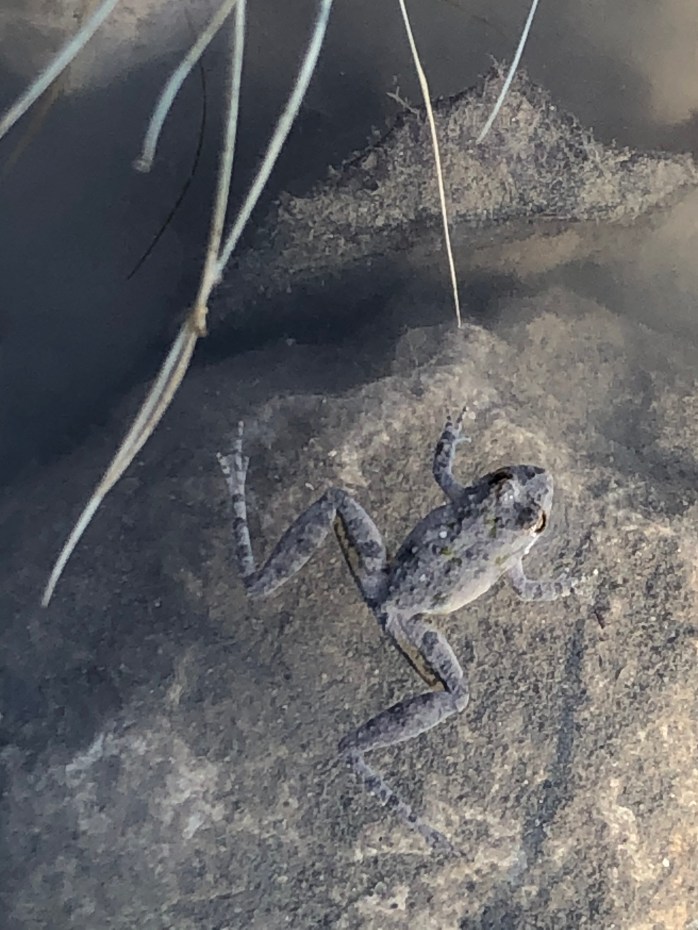

“Yeah, a Great Egret. I think I remember that they eat stuff that they can spear in shallow water, like fish or frogs. They’re so pretty when they fly.”

Elliott added, “I guess I can say something about the fish even though I don’t know what they are.”

“Ms. Martin said that was fine, that it was more important to put into words what you noticed – just what it looked like or sounded like. What did she say? ‘It helps you remember it and really notice and learn about it.’ So you could say they were silvery little shooting stars that flashed in the water, and that would be OK,” Kate commented.

Elliott smiled. “I remember – actually she’d really like that ‘shooting star’ bit, because she said it should capture how it came across to you, how you felt about it.”

They kept writing, including a little about the creek itself and the sparkling reflections of the sun when the shallow water ran over the rocks. There was the sound that water made when it ran fast and shallow, and an occasional bird call. They included the feel of the water, a cool swirl around their ankles and a slight push against their legs as they waded upstream (and Elliott could mention how hard they worked to keep their balance and that cool, sudden immersion when he fell in).

“I started to quit a few minutes ago,” Kate said, “but when you stop and think about it, there is so much to notice. I guess that was the point, huh, to get us to pay attention to all this.”

“Yeah,” Elliott answered, “How long do we have to keep going? I know she said there was no specific number of lines or words, but I keep thinking of stuff. If we weren’t doing this nature journal, I think I wouldn’t have noticed a lot of it.”

“Are you drawing anything?” Kate asked. “She said that would be good, too. Maybe I’ll draw your swirly clouds.”

“There’s that fossil snail or whatever that I saw back there. Maybe I can find another.” Elliott wandered around, looking at the exposed limestone, until he saw the exposed coil of a ribbed spiral shell, a limestone fossil embedded in the creek bed. He carefully worked it free and brought it back to where they were sitting.

“I see at least a piece of one of those every time I’m here,” Kate said. “All this used to be a sea bed, in prehistoric times, and these were kinda like a squid living in a snail shell, is what I heard.”

As Elliott began drawing, Kate continued, “We’re supposed to say if we’re grateful, or maybe write something like if we were talking to the place, telling it what we think. Let’s see … I’m grateful that you fell in.”

“Hey, we gotta wade back out of here, so don’t be so sure you won’t do the slip and slide and go for a swim.” At this point Elliott was hoping for it; paybacks were gonna be fun.

“Maybe this,” Kate went on, “’I’m glad we can visit this place, that it has so much cool stuff. It has had amazing animals since prehistoric times, and it’s still here. I hope people can wade this creek in a hundred years.’”

“I like that,” Elliott said. “Do you want to try this again, even after the assignment is done? I usually keep on the move, and writing and drawing kind of slows me down. But maybe it would be fun to try again.”

“It slowed you down but it made you think about stuff you would have walked right past,” Kate replied. “So we could go to that preserve with the open grasslands and woods and maybe if we wrote in the journal, we would notice more things and think about them in new ways.”

“OK, it’s a deal,” Elliott said. “We can give it a try.”

And on the way back … neither of them fell in the water. Elliott was a little disappointed.

(Recommending nature journaling might sound a little like a school assignment – which wouldn’t exactly get everyone rushing out to pick up a notebook and pen. So what is a good way to introduce it?

I decided that maybe a story would be a good approach, and in this story it literally is a school assignment. But it turns out well, and I’d like to think Kate’s and Elliott’s interest in trying some more journaling might also work out well. What I had in mind about the teacher’s prompts and suggestions to deepen their journaling is shown below – I took it along to the preserve and gave it a try. You could write something shorter; like Elliott said, there’s no prescribed number of words.)