At LBJ National Grasslands yesterday, new green growth emerged from the soil everywhere. In this ecotone, this blended margin between prairie and woodland, what had been the sandy brown floor was now turning green. In some places it was hidden beneath last year’s grasses, and in other places around trees and shrubs the scattered green was unmistakable. In areas that were recently burned, where the soil now had the most contact with the bright, warming sun, the new growth was strong.

It was March 19, the last day of winter. Tomorrow the Northern Hemisphere would be angled toward the sun just a bit more, reaching the vernal equinox. It would be the first day of spring. I spent most of the day at LBJ National Grasslands to say goodbye to winter in the biggest, quietest place I could wander through.

It was bright and sunny, as if the weather had already passed the equinox and was intent on spring. I soon shed the hoodie I started my walk with, as the breeze warmed a little and the sun was higher in the sky. By the end of the day I would have a mild sunburn and no regrets for having walked and sat in so much sunshine.

I started up on a ridge where limestone lies beneath shallow soil. In places, erosion exposes the limestone from an ancient sea bed filled with small oysters. I walked around one spot where water had exposed a small limestone shelf and eroded back under it. This was at the top of one of those places where the land drops away from the top of the cuesta or ridge and forms a long arroyo down the hillside. Big junipers, hackberries, and woody shrubs fill these places where the land concentrates rainfall.

On the top of the cuesta, prairie grasses grow where the soil is deep enough. In shallow soil, even in areas with bare limestone, you can find clumps of cacti such as the grooved nipple cactus with stems like rounded domes covered with spines. There are also prickly pear cacti whose pads in winter are colored in shades of faded brick red and pink. Elsewhere up on the ridge there are clumps of compass plant. I love those long deeply notched leaves that feel as if they were cut from stiff sheets of sandpaper.

A couple of hours later I was in the Cross Timbers woodland below the ridge, visiting a small pond. The breeze stirred ripples on its surface. The sunlight glittered brightly from the tops of those ripples, so that the pond’s entire surface seemed covered in sparkling jewels. When I let my focus soften, it was like a very fast twinkling of a field of stars. Even in simple places like this, the rest of the world drops away and there is only the pleasure of this moment in this spot. How we all long for such a refuge, and here it was.

Throughout the winter the sulphur butterflies persist and dance across dormant prairies and sunny glades, but today more insect life was awakening. In one spot I began to see orange butterflies. At the edge of a clearing, two of them encircled each other and seemed to catch an updraft, swirling straight up to the crowns of the surrounding trees. When one landed, I saw that it was a goatweed leafwing. Their deep orange wings are scalloped, edged in ashen gray and the forewing and hindwing come to points. Their interesting name is based on description and natural history. The host for their caterpillars is “goatweed” or croton, and when closed the wings look just like a dead leaf.

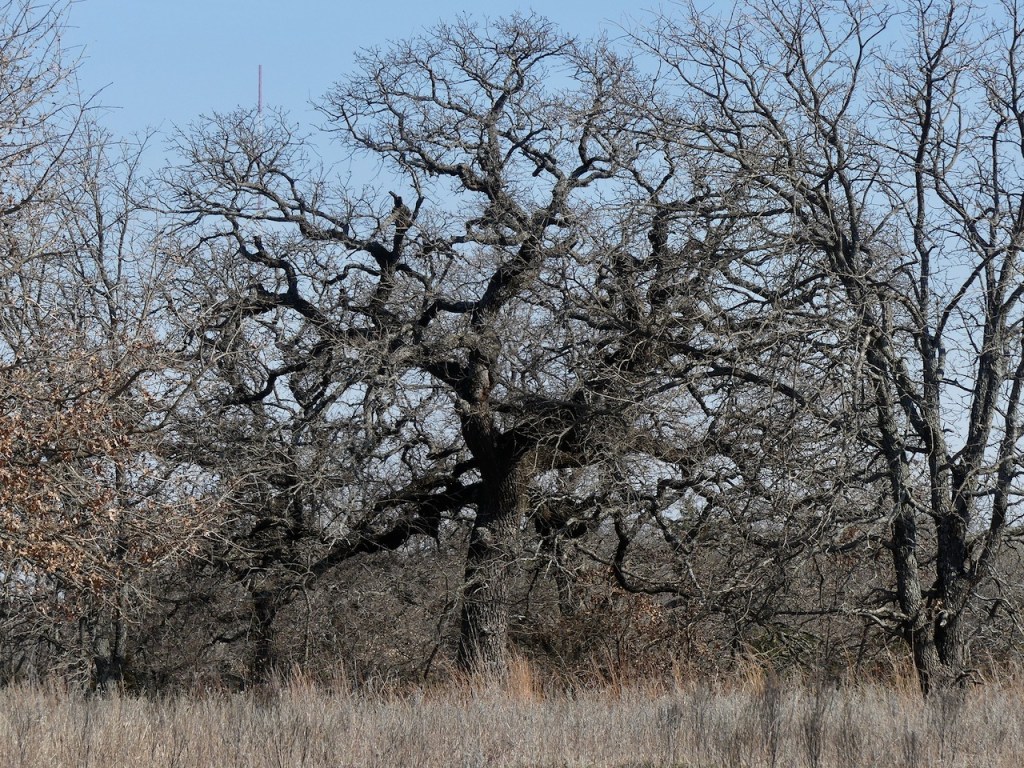

Finishing in this part of the grasslands, the practical but unimaginatively named unit 71, I drove to a couple of units near Alvord, including one of the beautiful and fragrant pine groves, and ended up in unit 30, one of my favorites. I let myself in through one of the green Forest Service gates and looked across the prairie and savannah toward the oak-juniper woodland.

Here was that wonderful down-sloping prairie with little bluestem, Indiangrass, and flowering plants scattered throughout. Then the trail reaches the trees and turns sharply, losing itself in junipers, post oaks and other trees. The woods frequently open into little prairie patches as well as a few little ponds. I know the features of this part of the trail and I enjoy each walk there. I thought about why the places within LBJ National Grasslands have such an attraction for me, these “same old” trails. But the affection for the place holds. Walking here is visiting old friends, so why would I tire of it? And when I walk through spots in the grasslands that are new to me I usually see familiar landscapes, just arranged differently. Some of the appeal for me is the sense of being able to spread out, to be unconfined in grasslands and woods that keep on going.

So goodbye to winter, and welcome spring! I’m ready for frog calls and purple coneflower, and those spring evenings with distant thunder. And eventually I’ll come to miss the earth tones of dormant vegetation and quiet winter afternoons. In time I will welcome winter back again.